Back in the mid-1980s (1983, to be specific) I was laid off from my first professional position as a geoscientist by an oilfield services company in Dallas called Core Laboratories. It was hard times in the industry—I’d survived the first three rounds of layoffs before the ax finally fell on me. It began a tough financial period for my husband and me, because we had just laid the foundations for a new house and he was in grad school, only working part time. I was essentially supporting us.

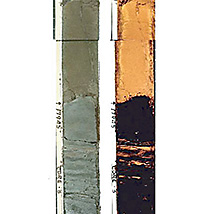

About 8 months after my layoff, I received a phone call from my old boss at Core Lab. Was I interested in a short-term contract job? Was I?! They had landed a project down in Venezuela with their state oil company, and it involved describing core. For those of you who don’t know, “core” is the round shaft of solid rock they drill out from an exploration well that samples the vertical layers through the zone of interest where oil might be found. They had hundreds of feet of this core, and they had just laid off the geologist who was a specialist in core description: me.

He told me the project would probably last around 3 weeks and would take place in Core Lab’s Maracaibo offices. I would go down with a fellow British employee named Chris, someone who was not a favorite of mine in the office (oh well). I finally asked the question that was in the forefront of my mind: “What does this pay?” When he casually answered, “Oh, about $350 a day,” I have to tell you, I about fell off my chair. To someone in the 1980s who has been unemployed for many months, that dollar figure sounded like manna from Heaven. I immediately said yes.

I was in my mid-20s and green, having never been out of the country before. I didn’t know what to expect and was lucky to even have a passport at the time. The company walked me through all the preparations. The trip took place from mid-November through early December, so I missed Thanksgiving at home with my husband and friends. I decided for the fantastic amount of money I would make, it was a price I was willing to pay.

However, working closely with someone who I’d previously had several unpleasant exchanges with was something I was worried about. Chris was one of several British expats I’d worked with who I came to think of as egotistical prigs. They were working in the US on green cards because unemployment rates in the UK were so high at the time. Yet they criticized the US (especially Texas) at every opportunity, and it really grated on me. “Biting the hand that feeds you” comes to mind, and Chris rubbed me the wrong way more than the others. In addition, most expat wives couldn’t work in the US. Chris’ wife was an attorney back home. Her bitterness over this situation, relegated to being a stay-at-home mom, over which she gave him an earful at night…well, he brought that to the office. He was often in a surly mood.

I don’t remember why now, but I was late boarding the plane to leave. I remember plopping down in the seat next to him, going, “Whew! Made it before they took off.” He just shrugged and said, “Well, either you’d show up or you wouldn’t. Wouldn’t make any difference to me.” That didn’t get us off to a great start. Obviously, our feelings were mutual.

This was not a glamorous introduction to international travel, as it turned out. My initial excitement at the idea of going someplace overseas, experiencing a new and exotic place, was quickly squelched. It was also my first introduction to offsite project work. We were expected to work 7 days a week—long, intense days, to crank out the work until the project was finished. It was costing our company a ton of money to put us up in hotels, three meals a day, the flights, etc., so we had to wrap it up as quickly as possible.

Also, hauling around boxes of core all day long was heavy work. They were usually slabbed in 4-foot lengths and three or four lengths to a box, so 12 to 16 feet per box. This was solid rock, folks. I can’t guess on the weight I was moving each day, but when I did this full-time for a living, the lab tech did it for me. I was exhausted at the end of each day.

I did love that I got to interact with the local Maracaibo Core Lab employees, and I did this increasingly as the days wore on. I ate lunch with them and enjoyed the exchanges as we each practiced our English and Spanish. They were friendly and curious about these two visitors from America. They had tons of questions about Dallas and living in the US. The lab manager, a woman, expressed a strong desire to “live in a developed country.” It was the first time to have it strike me that these citizens didn’t consider Venezuela a developed country.

The one thing on everyone’s mind was the presidential election about to take place on December 3—it was a hot topic of discussion. Venezuela was still a democracy back then and the citizens had a vested interest in who won. The two top candidates were Jaime Lusinchi and Rafael Caldera, with a ragtag lineup of others who had no chance. The campaign posters, the TV commercials, the arguments around the lunch table— it was all so familiar. And when Lusinchi won, there was euphoria and devastation by equal measure, as it should be. This is what a democracy feels like. These young people had real hope for their future. I was there; I saw it.

I think about those people today, what’s become of them. About 10 years after that trip, a series of coups, starting with Hugo Chavez, who overthrew their two-party system, have devastated the country’s economy and freedoms. Their oil economy has been exploited and devastated not only by Saudi Arabia’s manipulation of the market, but by their own government’s mishandling. Their latest president, Nicolás Maduro (who previously was Chavez’s vice president), has been accused of much worse: cocaine manufacturing and trafficking to the US, plus confiscation of US investments that developed their oil reserves.

This is no different than what Putin has done in Russia. He has confiscated billions in US assets and investments in their country, after US companies exited because of their invasion in Ukraine. Yet you don’t see Trump kidnapping Putin to “get our money and assets back.” Putin is his buddy and shares his imperialistic goals, so the double-standard there is easy for him to overlook. Besides, Venezuela was a much easier target.

We don’t know the whole truth of what has gone on inside that poor country. But we do know that it has been taken advantage of by dictators, bullies, and despots for the past 40-plus years who have enriched themselves at the expense of their citizens. Our President Trump is just the latest bully who has run roughshod over them. I only hope those Venezuelans who are cheering that Maduro is gone don’t believe the false promises, that “all this oil money is going back to where it belongs, to the great people of Venezuela.” Trust me, that’s not what Trump has in mind.

I’m very afraid for our country, about where we are headed. And for the people of Venezuela, who have already suffered too much.

As for Chris, and how that trip ended? I learned that even egotistical prigs are human beings. We eventually put our attitudes aside and called a truce for those 3 weeks, and even became friendly on that trip. It didn’t last long because I never worked with him again. But being forced to cooperate closely with someone where the project’s success depended on us—well, we had to rise to the occasion.

If you have thoughts about this post, you’re welcome to drop them in the Comments box below.

6 Responses

Excellent story, thanks for sharing. My thoughts and prayers are with the people of Venezuela. I only wish someone could come into our country and take our President. We are definitely facing some very scary times.

Kathy – that would probably be a “be careful what you wish for” scenario. God knows what we’d be in for afterwards. But I appreciate where you’re coming from. Thanks for commenting.

Gail

Gail, thank you, what an insightful story. And just like you have described, I have similar recollections of Venezuelan people from those remote years of their brittle democracy. I had several students from Venezuela learning English at the ESL program I taught in the early 1990s. They were so intelligent and eager to excel with great admiration for Americans. Just like you, I wonder what’s happened to their dreams and hopes they had cherished then, and how they had been forced into poverty by their corrupt leaders… and what really awaits them (and all of us) now.

I did recall that you taught ESL courses and wondered if you came across Venezuelan students. So glad you can relate to this story. It’s heartbreaking to see what’s going on – already their euphoria has turned to fear as the crackdown is happening by their government. Very scary times ahead for all of us.

Thanks for writing and sending this story. Your thoughts of what’s happening in Venezuela and the US now are exactly my beliefs. At least now I know someone agrees with me! By the way, I’m thinking you’re referring to the same Chris I’m familiar with. After Karl and I moved to California with Core Lab in 1981, they sent me back twice for month long training courses since I had transitioned to working in the lab with no experience. Chris taught both of those 4 week courses in Dallas. Your description of him seems exactly right, although I liked him and we got along great. But, I was a “student” and not working side by side like you.His courses were very tough for me and I had to study a lot. (we had weekly detailed written tests!) He was a good teacher and my studying paid off. I received a good grade and praise from him. All was so long ago, but I remember it all well. Thanks again for sharing!

Jackie, I’ll message you privately to see if this is the same Chris! That would be funny if it were, but I don’t recall him being involved with the labs. We shall see.